Desia Lodge

Desia Lodge

Desia Lodge

Die Pilgerinnen mit Stasi und Bubu, am Strand beim Lichterfest, noch ein Blick vom Grand Restaurant mit der Grand Road, Blick auf den majestätischen Jaganath, ein Heiliger und zwei Kunden im Chattapitri-Center.

Am frühen Morgen am Strand von Puri. Die Menschen setzen kleine “Boote” – eigentlich bloss Brettchen – mit Kerzen und Götterfiguren ins Meer aus. Ich tue es auch. Aber mein Boot kentert und die Kerzen verlöschen mit der ersten kleinen Welle. Wer es etwas grösser will, entlässt einen Heissluft-Ballon in den Himmel. Manche schaffen es weit übers Meer hinaus, bevor sie im Dunst verschwinden. Was gefeiert oder welches Fest begangen wird, weiss ich nicht.

Sie kommen jedes Jahr nach Puri, sie machen eine Pilgerfahrt und bleiben einen Monat, lauter alte Frauen. Gegen 1000 schlafen einem einzigen, grossen Raum, mit minimstem Komfort, eigentlich ohne allen Komfort. Der Geruch in dem industriellen, schmucklosen Betonblock ist streng. Aber sie haben ihren Glauben und der Aufenthalt in Puri ist ihnen höchst wertvoll. Am nächsten Tag werden sie wieder in ihre Heimatorte zurückkehren. Der Abschied sei jedes Mal mit viel Tränen verbunden, sagt Bubu.

Ankunft um 1 Uhr morgens, mit dem Taxi zum Shangri-La Eros. Beginn unserer Indienreise 2019.

Angekündigt war schlimmster Smog. Die Realität war weit entspannter. Schlechte Luft wohl, aber nicht weiter bemerkenswert. Übertriebene Berichte? Ein Wunder?

Besuch der grossen Moschee mit Yoginder. Grossartige, exotische Architektur mit den Zwiebelkuppeln aus Tausendundeinernacht.

Nachmittags im Khan-Market und Lunch im Townhouse.

Nachtessen im United Coffee House am Conought Square.

INTERVIEWER

What drew you to Baudelaire?

CALASSO

Baudelaire is the first non-Italian poet I truly read. In my grandfather’s house, there was a very large library and a beautiful studio. Before the studio, there was a room lined with books, and in the center was a big table with papers. As a kid I was there very often, looking at things I didn’t know anything about, and there I found a copy of Les fleurs du mal, in a fine edition done by Crès in the twenties. Crès was a very elegant publisher from a typographical point of view. I stole the book from my grandfather. It is the first and only book I have ever stolen. My grandmother noticed it because she had an eagle eye—besides, the book was inscribed to her by my grandfather. So she did something slightly perverse. She gave it as a gift, not to me, but to my mother. My mother, in her very last years, gave it to me. So there are three inscriptions in the book, and the last one is rather recent.

When I stole it, I must have been twelve. I was starting to learn French and, of course, I was attracted by the title—it was irresistible. I always had a special sense for Baudelaire, which I never had for any other poet—something more direct, more intimate. And I have to admit that the Folie Baudelaire was the book I wrote with the most ease.

INTERVIEWER

How long did it take you?

CALASSO

It took some time, because what you read now is only a part of the whole—I took out so many things. The book is not only about Baudelaire, but about the wave that, influenced by him, ran through France in the nineteenth century, both in literature and in art. Baudelaire was far more than a great poet. He established the keyboard of a sensibility that still lives within us, if we are not total brutes. The Tiepolo book was a big branch of this tree, and the branch detached itself because I felt it was a book and it had to be alone. So Tiepolo Pink was published before the Folie. I can’t judge exactly how long it took, perhaps around five years.

INTERVIEWER

That’s not exactly a rush.

CALASSO

Consider that L’ardore, my latest book, is something that has gone on with me since Ka, so more or less fifteen years. No other book of mine has taken so much time.

Peter Robinson von der Hoover Institution leitet eine Gesprächsrunde mit David Gelernter, David Berlinski und Stephen Meyer. Thema ist der Artikel von Gelernter in der Claremont Review of Books mit dem Titel “Giving up Darwin”. Geführt wurde die Diskussion in Fiesole im Juni 2019. Leider erfährt man nicht, wie es zu dieser Runde an diesem Ort gekommen ist.

Berlinski, jetzt wohl in den 80, mit Stock, Stiefel, T-Shirt und ärmelloser Jeansjacke.

Eine grossartige Gesprächsrunde.

Die Tür aufhalten, heraneilenden Krankenwagen Platz machen – Fehlanzeige. In unserer modernen, auf Autonomie bedachten Zeit scheint gutes Benehmen nicht gefragt. Doch Manieren haben einen wichtigen Sinn, sagt der Soziologe Tilman Allert. SWR2 Aula.

Zum Text der Sendung

Website

Podcast mp3

Die erste Hälfte der zwei Staffeln mit je 12 Folgen von Shtisel gesehen. Sehr eindrücklich. Eine Familie, Menschen, fest eingebunden in ihrem Glauben. Und die Frage stellt sich: was gibt ihnen ihr Glaube, ihre Rituale und endlosen Vorschriften? Haben sie den Ungläubigen (jeder Couleur) etwas voraus in Sachen Sicherheit, Zuversicht, Lebensfreude? Der Film verneint es. Allerdings auch: was haben die Glaubenslosen an Vorteilen? Was ist der Preis, den sie (wir) für die tatsächliche oder scheinbare Freiheit bezahlen?

Am 19. Februar ist Karl Lagerfeld gestorben. Einer der kreativsten, gescheitesten Zeitgenossen. Gescheit im Sinne von lebensgescheit. Aus dem Buch ein paar zufällige Zitate:

You have to lead your life according to your ideas. Spend all your money and live life in line with what you are fighting for.

I hate it when rich people try to be Communists. I think that’s obscene.

If you throw your money out of the window, do it with passion. Don’t say ‚you shouldn’t do that, that’s bourgeois.

Luxury is freedom of spirit, independence, basically political incorrectness.

The essential thing is not that people should sit on their money. It has to come out of their pockets.

What is this obsession always to be with people. Solitude is the biggest luxury.

WeiterlesenMit Hape in der Füssli-Ausstellung (hallo!). Sie wurde verlängert, statt bis 12.2. bis 17.2. Vieles da, leider nicht die Nachtmahr. Sehr theatralisch, grosse Gesten, grosse Gefühle – Entsetzen, Furcht, Wahn, Visionen. Helden, Götter und lauter edle, bleiche Frauen. Schön und grosszügig eingerichtet, wenig Publikum.

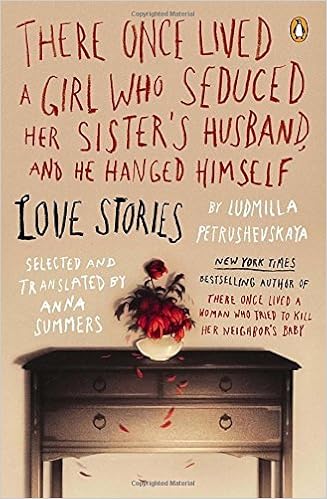

Die Kurzgeschichte in der Paris Review Winter 2018. Zwei alte, mausarme Schwstern leben in einer kleinen Wohnung. Sie überleben mit dem absoluten Minimum. Das heisst, bis eine dem Tod nahe ist. Die andere, jüngere streicht ihr als letzte Hoffnung eine Paste auf die Lippen, glaubt dann, dass sie damit die ältere vergiftet habe und tut sich deshalb verzweifelt das selbe an. Aber sie sterben nicht, sondern in magischer Metamorphose erwachen sie aus einer Ohnmacht als Mädchen von 12 und 13 Jahren.

Die Kurzgeschichte in der Paris Review Winter 2018. Zwei alte, mausarme Schwstern leben in einer kleinen Wohnung. Sie überleben mit dem absoluten Minimum. Das heisst, bis eine dem Tod nahe ist. Die andere, jüngere streicht ihr als letzte Hoffnung eine Paste auf die Lippen, glaubt dann, dass sie damit die ältere vergiftet habe und tut sich deshalb verzweifelt das selbe an. Aber sie sterben nicht, sondern in magischer Metamorphose erwachen sie aus einer Ohnmacht als Mädchen von 12 und 13 Jahren.

Soviel Magie und Realismus zusammen ist wohl nur in Russland möglich. Witz und Tragik so nah beisammen.

Wikipedia: Lyudmila Stefanovna Petrushevskaya (Russian: Людмила Стефановна Петрушевская; born 26 May 1938) is a Russian writer, novelist and playwright. She began her career writing and putting on plays, which were often censored by the Soviet government, and following perestroika, published a number of well-respected works of prose.

She is best known for her plays, novels, including The Time: Night, and collections of short stories, notably There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby. In 2017, she published a memoir, The Girl from the Metropol Hotel.[1] She is considered one of Russia’s premier living literary figures, having been compared in style to Anton Chekhov[1] and in influence to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.[2] Her works have won a number of accolades, including the Russian Booker Prize, the Pushkin Prize, and the World Fantasy Award.[3]

Her creative interests and successes are wide-ranging, as she is also a singer and has worked in film animation, screenwriting, and as a painter.[4]

INTERVIEWER [Paris Review]

Some people think that a longing for God underlies your works.

DE BEAUVOIR

No. Sartre and I have always said that it’s not because there’s a desire to be that this desire corresponds to any reality. It’s exactly what Kant said on the intellectual level. The fact that one believes in causalities is no reason to believe that there is a supreme cause. The fact that man has a desire to be does not mean that he can ever attain being or even that being is a possible notion, at any rate the being that is a reflection and at the same time an existence. There is a synthesis of existence and being that is impossible. Sartre and I have always rejected it, and this rejection underlies our thinking. There is an emptiness in man, and even his achievements have this emptiness. That’s all. I don’t mean that I haven’t achieved what I wanted to achieve but rather that the achievement is never what people think it is. Furthermore, there is a naïve or snobbish aspect, because people imagine that if you have succeeded on a social level you must be perfectly satisfied with the human condition in general. But that’s not the case.

Weiterlesen

Er gehört zu meinen Intellektuellen-Helden (heroes) – David Berlinski. Elegant, entspannt, eloquent formuliert er seine Vorbehalte zum Darwinismus.

Die eingeblendeten Bibelsprüche am Schluss darf man getrost vergessen. Berlinski selber dürfte kaum Freude daran haben. Er bezeichnet sich als Atheist.

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani beschreibt in der NZZ einen offenkundige, selten thematisierten Zustand. Ausgehend von einem Architekturvortrag vor über 100 Jahren, gehalten von einem Hendrik Petrus Berlage, schreibt Lumpagnani:

Es war der niederländische Architekt Hendrik Petrus Berlage, der vor über hundert Jahren diese Auffassung vertrat, und zwar in einem Vortrag mit dem Titel «Baukunst und Impressionismus». Bis dahin waren die städtischen Häuser Gebilde mit komplex artikulierten Hüllen gewesen. Sie waren in Hauptteil, Basis und Attika gegliedert, die jeweils anders gestaltet und oft auch aus anderen Materialien hergestellt waren: der Sockel widerstandsfähig, weil am exponiertesten, und schwer, um Solidität zu vermitteln, die Attika leicht und licht, allenfalls mit kräftigem Gesims, um den oberen Gebäudeabschluss zu markieren. Dazwischen waren die Fenster rhythmisch in die Fassade eingeschnitten, wobei Rahmen oder Faszien den Übergang zwischen Fläche und Öffnung thematisierten.

Die Fensterbänke standen stärker vor, um Wassernasen zu vermeiden, aber auch um dem Fenster mehr Halt in der Wand zu verleihen. Die Fensterläden waren in die Gesamtkomposition integriert. Flächige oder plastische Zierelemente unterstrichen sie und fügten dekorative und erzählende Dimensionen hinzu, die das Haus mit seiner Nutzung, seinem Bauherrn oder einfach nur seiner Zeit verknüpften. All das, so Berlage, war nunmehr anachronistische Verschwendung und würde vom neuen, rasanten Lebensrhythmus dahingerafft werden.

Von da vorwärts zur Gegenwart, mit Häusern und Städten, die gebaut wurden für die Insassen “rasender Automobile”, welche für architektonische Feinheiten weder Zeit noch das Auge haben.

Weiterlesen25. bis 29. Januar Paris, Spira im Dojon. Übernachtung im Monterosa, Rue de la Bruyère.

Am 28. im Louvre. Zur Erinnerung der riesige Veronese (Hochzeit von Kanaan). Im selben Saal wie die Mona Lisa. Nur halt so viel interessanter. Der etwas leblose Jesus in der Mitte mit seinem durchdringenden Blick. Ganz links (hier nicht sichtbar) die Braut mit Bräutigam. Dazu die Hunde, die Musiker und tausendundein Symbole. Grosses Kino, wie man so sagt.

Unten die Gilets Jaunes im Original auf dem Boulevard Voltaire. Ganz passend.

Nachtessen jeweils mit Dora und Urs. Auf dem Bild im edlen Vegi-Italiener beim Gare du Nord.

Paris: Kein Bobo-Aufstand, keine Lehrer, Sozialarbeiter, Studenten, Professoren, sondern die Leute vom Land. Nicht das Kleinbürgertum, die Proletarier melden sich, mit ihren Parolen und Methoden, und das Kleinbürgertum, welche die Meinungsdominanz ihr eigen nennt, ist entsetzt. Interview in spiked mit Christopher Gully.

Back in 2014, geographer Christopher Guilluy’s study of la France périphérique (peripheral France) caused a media sensation. It drew attention to the economic, cultural and political exclusion of the working classes, most of whom now live outside the major cities. It highlighted the conditions that would later give rise to the yellow-vest phenomenon. Guilluy has developed on these themes in his recent books, No Society and The Twilight of the Elite: Prosperity, the Periphery and the Future of France. spiked caught up with Guilluy to get his view on the causes and consequences of the yellow-vest movement.

spiked: What is the role of culture in the yellow-vest movement?

Guilluy: Not only does peripheral France fare badly in the modern economy, it is also culturally misunderstood by the elite. The yellow-vest movement is a truly 21st-century movement in that it is cultural as well as political. Cultural validation is extremely important in our era.

One illustration of this cultural divide is that most modern, progressive social movements and protests are quickly endorsed by celebrities, actors, the media and the intellectuals. But none of them approve of the gilets jaunes. Their emergence has caused a kind of psychological shock to the cultural establishment. It is exactly the same shock that the British elites experienced with the Brexit vote and that they are still experiencing now, three years later.

The Brexit vote had a lot to do with culture, too, I think. It was more than just the question of leaving the EU. Many voters wanted to remind the political class that they exist. That’s what French people are using the gilets jaunes for – to say we exist. We are seeing the same phenomenon in populist revolts across the world.

spiked: How have the working-classes come to be excluded?

Ein Netflix-Abend mit den Meyerowitz Stories. Wikipedia weiss dazu:

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)[1][2] is a 2017 American comedy-drama film directed and written by Noah Baumbach. The film stars Adam Sandler, Ben Stiller, Dustin Hoffman, Elizabeth Marvel and Emma Thompson, and follows a group of dysfunctional adult siblings trying to live in the shadow of their father.

The Meyerowitz Stories was selected to compete for the Palme d’Or in the main competition section and also won the Palm Dog award at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival.[2][3][4] It received positive reviews from critics, who praised Baumbach’s script and direction as well as the performances, with Sandler especially singled out for praise. It was released in select theaters and on streaming by Netflix on October 13, 2017.

Jüdisches Künstler-Milieu in New York. Erinnert an die frühen Woody Allen-Filme. Möglichst nah dran am Alltag, Dramatik des Alltäglichen. Gescheit und unterhaltsam. Nur Emma Thompson kommt mit der Rolle nicht richtig zurecht. Auch ihr Outfit ist zu übertrieben. Musik von Randy Newman. Hochgelobt und mit vielen Auszeichnungen – auch in Cannes.

In der NZZ wird die Frage nach der Realitätsaussage der Quantenmechanik gestellt. Offenbar wird die Realität eindeutig erst durch die Beobachtung konstituiert. Das scheint unbestritten. Doch bleibt unklar, was unter Realität hinter der Beobachtung überhaupt zu verstehen ist. Im Artikel wird ausgeführt:

Das Kernstück der heutigen Quantentheorie ist Schrödingers Wellen- oder Zustandsfunktion. Nach einem breiten Konsens unter Physikern enthält sie die vollständige Information über das betreffende Quantensystem. Sie beschreibt das Spektrum der möglichen Messwerte – etwa Position, Energie, Spin eines Teilchens. Aber im Gegensatz zur klassischen Situation existiert dieses Teilchen erst in einem eindeutigen realen Zustand, wenn wir es gemessen haben.

Das stellt nun den Realismus des klassischen physikalischen Weltbilds von den Füssen auf den Kopf. In diesem Weltbild existieren die physikalischen Systeme unabhängig von den Messinstrumenten, und die Instrumente sind einfach Informationslieferanten. John Archibald Wheeler, einer der phantasievollsten Physiker des 20. Jahrhunderts, hat darin eine der grossen Fragen der modernen Physik geortet. Ein reales physikalisches System bezeichnet er als «It»; die Information in der Zustandsfunktion als «Bit». Klassisch sagen wir: Da ist ein Teilchen in einem bestimmten Zustand – ein It –, und wir messen an ihm bestimmte Grössen: «Bit from It». Quantentheoretisch sagen wir: Wir messen bestimmte Grössen und schliessen daraus, dass sich da ein Teilchen in einem bestimmten Zustand befindet: «It from Bit». Ein Lichtpunkt auf dem Bildschirm, ein elektrischer Puls, ein Klick im Detektor: Das sind die Antworten des Apparats, die informationellen Atome der Realität.

«It from Bit» hat das Zeug zu einer konzeptuellen Revolution. Die Welt dreht sich nicht mehr um ihre materiellen, sondern um ihre informationellen Elemente. Warum ist die Welt quantisiert? «It from Bit» gibt uns eine trivialgeniale Antwort: weil unsere Fragen und Antworten letztlich quantisiert sind, sich auf abzählbar viele binäre Entscheide zurückführen lassen: Fliesst ein Strom oder nicht? Handelt es sich um die Spur eines Antiprotons? Unter das Ja-oder- Nein-Niveau kommen wir nicht.

Anton Zeilinger, der Quanteninformatiker aus Wien, der heute Wheelers Idee im Labor weiterführt, schreibt, dass «wir bewusst nicht mehr fragen, was ein elementares System eigentlich ist. Sondern wir sprechen letztlich nur über Information. Ein elementares System (. . .) ist nichts anderes als der Repräsentant dieser Information, ein Konzept, das wir aufgrund der uns zur Verfügung stehenden Information bilden.» Zeilinger stellt sogar das radikale Postulat auf: «Wirklichkeit und Information sind dasselbe.» Man könnte vom Postulat des informationellen Realismus sprechen: Am Anfang war das Bit.

Der klassische Idealismus und mit ihm Advaita wird sagen, die Beobachtung und das Beobachtete sind eins. Esse est percivi, wobei wir wieder bei Berkley wären. Oder die eigene Einsicht: Es ist uns keinerlei Möglichkeit zur Unterscheidung gegeben. Die Suche nach dem It führt nirgendwo hin.

Oleg Karavaichuk (1927-2016), Russischer Pianist und Komponist. Ich bin durch einen Film auf Arte auf ihn gestossen. Der spanische Film wurde ein Jahr vor seinem Tod gedreht.

Ein merkwürdiger Mensch. Man weiss nicht ob Mann oder Frau, je älter je fraulicher, vielleicht. Mit einer Musik zwischen allen Stühlen. Walzer und Minimal mit “emanzipierter Dissonanz” gemäss Schönberg. Grossartige Musik. Sehr stark.

Beeindruckend, berührend in seiner absoluten Hingabe an die Musik.

Mit russischer Schreibweise auch auf Spotify mit einigen Aufnahmen aufzufinden.

Just like his compositions that mix consonance and dissonance, Oleg Nikolaevich Karavaichuk is an ever-changing character in this affectionate portrait, which retains a certain mystery. When the androgynous octogenarian passes through the corridors of the Hermitage Palace to sit at Tsar Nicholas’s magnificent piano, his remarks on the contrast between the snow-covered streets of Saint Petersburg and the architectural and historical force of the place set the tone of the film: each digression in his conversation and music is anchored in the intensity of his feeling for textures and matter. So Oleg concludes a political anti-Putin lament with a note of olfactory melancholy: “Why does the fruit at the market no longer have a smell?” What indeed, in today’s Russia, no longer touches the senses, or even the sentiments?

The pianist, who wrote scores for Sergei Parajanov and Kira Muratova, sometimes seems almost delirious, but above all he incarnates in a single body his country’s recent upheavals. The disaffection he mentions is echoed by the splendid shots of his deserted dacha, where the library is intact but for a Lenin lying forgotten on the floor. With his high-pitched voice and often tactile metaphors, this artist – who seems to have traversed the centuries – is in himself a Russian ark. (Charlotte Garson)

Nach der verklärten Nacht ein weiteres Vordringen zu Schönberg: Das Streichquartett Nr. 1 und die sechs kleinen Klavierstücke. Zum Streichquartett schreibt Greenberg:

An important work is Schoenbergfs String Quartet No. 1 in D minor of 1905. It is a long piece cast in four continuous movements. Three aspects of the quartet emphasize its modernity. First is its incredible polyphonic intensity: Each of the four instruments of the quartet is a soloist much of time. Second, Schoenbergfs phrases are not balanced, poetic phrases with antecedent and consequent structures. Rather, they are prose.like, open ended, and rhapsodic. Third, the variety of string quartet textures Schoenberg employs is mind.boggling.

Zum frühen Werk schreibt er:

Schoenberg believed in melody more than anything else. As the first years of the 20th century progressed, he ceased to believe in the tonal harmonic system. By 1908, Schoenberg had come to the conclusion that functional harmony stifled and constrained melody by forcing it to adhere to what he believed were “artificial” constructs: chords built by stacking thirds and chord progressions based on harmonic motion by perfect fifths.

Schoenberg began to perceive his artistic mission as that of a simplifier, no small irony given how difficult his music can be for the uninitiated listener. Between 1908 and 1913, Schoenberg composed a series of experimental works that remain among the great masterworks of the 20th century, including the Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909), Erwartung, Op. 17 (1909); Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21 (1912), and Die glückliche Hand (1913).

To describe his work, Schoenberg preferred the word pantonal, implying that his music embraced a sort of all‑encompassing ur‑tonality. This course will simply call it nontonal.

Du muss angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar zu veröffentlichen.